The rugby edition uses fewer variables than its cousin, primarily kick location and footedness of the kicker, but it does differ in that many of the simpler attempts have expectations that approach 100%.

Therefore, many kickers have a near perfect conversion rates from a particular distance and angle.

One choice that is common to each model is how to express a player's over or under performance and typically the percentage above or below the expectation of an average kicker is used. Or occasionally a +/- differential expressed in goals or points in the case of rugby.

Repeatability is always a desirable quality of a metric that professes to capture aspects of player talent. Performance levels may fluctuate for a variety of reasons, injury, aging or simply random variation, but if a model is to be useful we would expect to see some season on season correlation between the metrics we are recording.

Expected goals models profess to show those who are performing above the general average expectation and often this is used to illustrate above average ability, although inevitably buoyed also by luck.

However, often these levels of over performance are not repeated in future seasons, inevitably calling into question the validity and usefulness of a particular model.

Inevitably these models lack all of the inputs to adequately quantify the abilities we are trying to measure, but part of the problem may be down to how the outputs are expressed, especially if some chances are highly likely to be successfully taken.

Imagine an idealised example from soccer.

A player takes five shots at goal, each has a 20% chance of resulting in a goal, so the average expectation is that he scores once. In the field he scores twice, so he's doubled his expected goals, scoring 200% of an average player.

In terms of goal differential, he's +1 goal.

His next five attempts are much better chances with an 80% chance of scoring, akin to the relatively automatic conversions I see in rugby.

He should score on average four goals, but buoyed by being dubbed a hot striker on BT sport he converts all five. He's perfect, he couldn't have scored any more.

In terms of differentials, he's now plus 2. The average player would expect to score 5 from his last 10 attempts , but our player has scored 7. He has been rewarded for his perfection by seeing his differential above average increase from +1 after 5 attempts to +2 after 10.

How does an index approach reward his recent spree?

After 5 20% attempts, his two scores were scoring at twice the expected average rate (2 goals instead of just 1). But once we include his arguably more impressive perfect five from five 80% chances it actually reduces his rate of over performance from twice the average to 1.4 times the average rate (7 goals instead of an expected 5).

Two ways of expressing the output from an expected goals model. Differentials reward a run of perfection by improving the rating from 1 to 2, while a rate approach decreases the rating from 2 to 1.4.

Intuitively the latter would appear flawed when applied to a player who attempts high value chances and the quality of your model notwithstanding, how you chose to express the output may impact on your chances of finding year on year correlations.

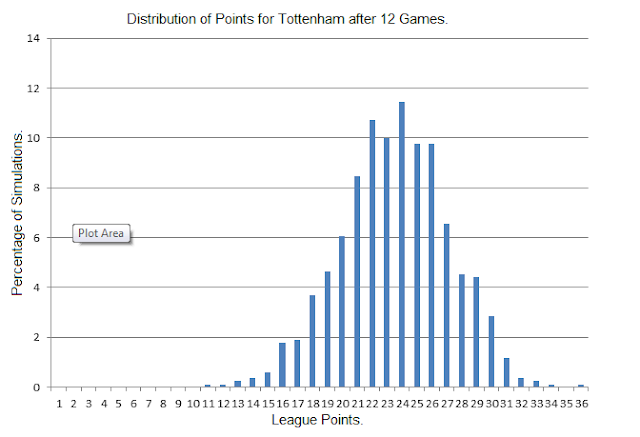

A third alternative is to run a simulation of the individual expectation for each attempt and see how many trials are as good or better than the result achieved by the player under scrutiny.

25% of true average players would score two or more from 5 20% attempts just by luck, but only 11% would manage 7 from the ten attempts further described.

A player who continually finds himself in this lucky subset, may simply be better than the average striker and using an approach that accounts for the distribution of the quality of his chances may not see his rate bounce around if he has a bout of successful goal hanging.