The use of data to inform and illuminate is gradually creeping into the mainstream media with varying degrees of success. The best examples legitimately combine excellent writing, an engaging narrative and data collection and interpretation, to produce a finished item that can be enjoyed and debated on many levels.

The Guardian's Sean Ingle currently sets the bar at a high level.

The most recent example sees Sports Writer of the Year, Martin Samuel adding a dash of data to his piece on Chelsea's penalty record in the Premier League in the Mail Online.

Mourinho has complained loudly that his team are hard done by when penalties have failed to be awarded this season and Samuel cites statistical analysis carried out by Opta to support Jose's assertions. (Although to be fair to Opta, they appear to have merely undertaken the collection part of the analysis and any interpretation of the data appears to be wholly the work of Samuel).

Samuel's approach follows a well trodden route. It uses Chelsea's rate of being awarded spot kicks in the Premier League this year (1 per 13 games in 26 matches) compared to their rate in the Champions League ( 1 per 1.8 games in 7 matches) and also against those of their English rivals from the CL and domestically.

Samuel then uses the "whopping additional 11.2 games needed to win a penalty in the Premier League" as the main "corroborative" evidence that Chelsea are getting a raw deal.

Firstly, referees appear to have particular regional traits, especially in areas such as on field discipline, where card make ups can vary considerably from one country to another. Therefore, is shouldn't be a surprise if Chelsea's CL refs, comprising Croatian, Spanish, Italian, Dutch Turkish, Norwegian and Swedish may differ in their interpretation of what constitutes a penalty kick compared to their Premier League counterparts.

Secondly, the level of competition faced by Chelsea, particularly in the CL group matches hasn't been very strong and more spot kicks tend to be conceded by teams which are vastly inferior to their opponent.

The Euro Club Index rated the average of Chelsea's three group opponents at 2555 ranking points, the equivalent of a group made up of three teams of the average quality of a Stoke City. The easiest team from the group, NK Maribor currently rank 208th in the Index, inferior to virtually every current Premier League team.

(As an initial stage to the statistical analysis of Chelsea's seven game Champions League campaign, offered without any additional interpretation, two of Chelsea's four CL penalties came in their 6-0 defeat of Maribor).

But the main issue we should take with this mainstream article is in the use of headline penalty award rates derived from sample sizes that are unequal and limited in size.

Events do not happening in neat evenly spaced distributions. For example a fair coin which dutifully records a head followed by a tail should be treated with suspicion, rather than a confirmation that it is fulfilling an obligation to land a head or tail with equal likelihood.

Chelsea could easily have a typical Premier League likelihood of receiving penalty kicks of around one every 4.7 games and be awarded just two in 26 matches. The chances of this occurring or worse is around 7%. And the chances of any top side suffering this apparent injustice is greater still.

Relatively uncommon events will inevitably produce prolonged periods when they do not occur and others when they appear unnaturally clumped together, and this does not in itself provide evidence that a team is getting a raw deal.

You could have used a similar seven game Premier League sample to show have hard done to Manchester City were when they went into their 8th of the season match against Spurs without a penalty to their name.

90 minutes later, they had three.

Randomness is a much more likely candidate than conspiracies to explain Chelsea's record of penalty awards in 2014/15.

Friday, 27 February 2015

Saturday, 21 February 2015

Place Kicking and Six Nations Grand Slams.

In this previous post I looked at the effect of place kicking ability on the result of a single rugby union match based on rating kickers with a simple logistic regression model. The results highlighted the development of George Ford, England's current number 10, from his entry into the game with Leicester to his current position as an international kicker.

A more useful application of kicker ratings in rugby union is to compare the range of match outcomes over a competition, such as the Six Nations, bought about through the natural variation around a kicker's likely talent, as well as the effect of replacing that talent with an average value from the current pool of place kickers.

In this way we might usefully show the contribution made to a country's success by their regular kickers compared to that expected from an average replacement level of kicking ability.

The Grand Slam isn't a particularly rare event in the history of the Five and now Six Nations, it has been won in 40% of the tournaments since 1947 and was last won in 2012 by Wales.

With the exception of half a dozen kicks from Rhys Priestland, Leigh Halfpenny was the place kicker for each of Wales' five 2012 victories. England relied upon Owen Farrell, Scotland, Grieg Laidlaw and Ireland, Jonathan Sexton, while France mixed and matched between four different kickers and Italy used three different kickers.

I have used the kicking stats for each of the kickers from their previous season, both at club and international level. The majority of the Six Nations kickers had well in excess of 100 penalty or conversion attempts in that period and these kicks have been used to project how successful each kicker would expect to be when faced with the kicking opportunities during the Six Nations based on the difficulty of each kick.

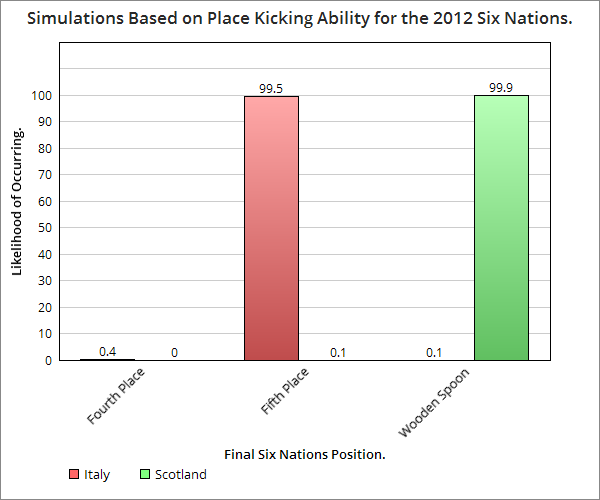

I've then simulated the probabilistic outcome of all 153 kicks made during the competition and re scored all 15 matches by adding the outcome of simulated place kicks to those points scored from tries and open play kicks. Each "tournament" is replayed 10,000 times.

Wales won three of their five matches by a converted try or less, but even over 10,000 place kicking match simulations they remain the overwhelmingly most likely side to have taken the championship. Although the possibility that a single bout of unlucky place kicking could lead to a single defeat is clearly demonstrated by the likelihood of a Grand Slam falling to 73% compared to a 97% title chance.

Wales had by far the best points differential, which is used as a tie breaker if league points are equal and this advantage spills over into the simulations when they are tied with others on eight points.

There was a tiny possibility that England could have won the Grand Slam, although they were mostly competing with Ireland for second spot.

Ireland's comprehensive defeat by England effectively ended their chances of "winning" a virtual Slam, no amount of excellent Sexton place kicking could over turn the 10 points to 0 try scoring differential. But their heavy actual and potential defeat of Italy kept alive their chances of second spot in the simulations. This also indicates the large role played by the weaker sides in determining positions at the top of the final table under the current regulations.

Rhys Priestland began the tournament as Welsh place kicker and although statistically inferior to Halfpenny in the previous season he would expect to kick better than his poor, small sample efforts in 2012. Because of his poor start, Halfpenny remained Wales' primary place kicker during 2012.

In the plot above, I've simulated Wales' 2012 results firstly with Priestland and Halfpenny as the place kickers, each with the expected ability that they had demonstrated in 2011 for Wales and the Scarlets and the Blues respectively.

I've then re run the simulation using the modeled kicking ability of an average, regular kicker from the 2011 season to see the potential cost of playing with an average, rather than exceptional kicker, in the case of Halfpenny.

An average kicker costs Wales about two championships per 100 simulated trials, falling from around 97 with their actual choice of kickers to 95 with an average replacement. So Wales' 10 tries shared around each of their five games, bettered only by Ireland's 13 appears to make them worthy champions, almost regardless of kicking ability. However, Grand Slams, which are unforgiving of a single slip up, fall by six per hundred from 73 to 67 with a par kicker.

Probably just as importantly, England win one Slam per 100 when Halfpenny takes the majority of Welsh kicks, but the agony/ecstasy is doubled to two if a par kicker takes the field for the Welsh.

A more useful application of kicker ratings in rugby union is to compare the range of match outcomes over a competition, such as the Six Nations, bought about through the natural variation around a kicker's likely talent, as well as the effect of replacing that talent with an average value from the current pool of place kickers.

In this way we might usefully show the contribution made to a country's success by their regular kickers compared to that expected from an average replacement level of kicking ability.

The Grand Slam isn't a particularly rare event in the history of the Five and now Six Nations, it has been won in 40% of the tournaments since 1947 and was last won in 2012 by Wales.

With the exception of half a dozen kicks from Rhys Priestland, Leigh Halfpenny was the place kicker for each of Wales' five 2012 victories. England relied upon Owen Farrell, Scotland, Grieg Laidlaw and Ireland, Jonathan Sexton, while France mixed and matched between four different kickers and Italy used three different kickers.

I have used the kicking stats for each of the kickers from their previous season, both at club and international level. The majority of the Six Nations kickers had well in excess of 100 penalty or conversion attempts in that period and these kicks have been used to project how successful each kicker would expect to be when faced with the kicking opportunities during the Six Nations based on the difficulty of each kick.

I've then simulated the probabilistic outcome of all 153 kicks made during the competition and re scored all 15 matches by adding the outcome of simulated place kicks to those points scored from tries and open play kicks. Each "tournament" is replayed 10,000 times.

Wales won three of their five matches by a converted try or less, but even over 10,000 place kicking match simulations they remain the overwhelmingly most likely side to have taken the championship. Although the possibility that a single bout of unlucky place kicking could lead to a single defeat is clearly demonstrated by the likelihood of a Grand Slam falling to 73% compared to a 97% title chance.

Wales had by far the best points differential, which is used as a tie breaker if league points are equal and this advantage spills over into the simulations when they are tied with others on eight points.

There was a tiny possibility that England could have won the Grand Slam, although they were mostly competing with Ireland for second spot.

Ireland's comprehensive defeat by England effectively ended their chances of "winning" a virtual Slam, no amount of excellent Sexton place kicking could over turn the 10 points to 0 try scoring differential. But their heavy actual and potential defeat of Italy kept alive their chances of second spot in the simulations. This also indicates the large role played by the weaker sides in determining positions at the top of the final table under the current regulations.

Rhys Priestland began the tournament as Welsh place kicker and although statistically inferior to Halfpenny in the previous season he would expect to kick better than his poor, small sample efforts in 2012. Because of his poor start, Halfpenny remained Wales' primary place kicker during 2012.

In the plot above, I've simulated Wales' 2012 results firstly with Priestland and Halfpenny as the place kickers, each with the expected ability that they had demonstrated in 2011 for Wales and the Scarlets and the Blues respectively.

I've then re run the simulation using the modeled kicking ability of an average, regular kicker from the 2011 season to see the potential cost of playing with an average, rather than exceptional kicker, in the case of Halfpenny.

An average kicker costs Wales about two championships per 100 simulated trials, falling from around 97 with their actual choice of kickers to 95 with an average replacement. So Wales' 10 tries shared around each of their five games, bettered only by Ireland's 13 appears to make them worthy champions, almost regardless of kicking ability. However, Grand Slams, which are unforgiving of a single slip up, fall by six per hundred from 73 to 67 with a par kicker.

Probably just as importantly, England win one Slam per 100 when Halfpenny takes the majority of Welsh kicks, but the agony/ecstasy is doubled to two if a par kicker takes the field for the Welsh.

Sunday, 15 February 2015

How Important Is Place Kicking in Rugby Union?

The importance of the boot in rugby union is increasingly evident. Not only as a means of gaining territory, but most obviously as a way of advancing the scoreboard through both penalties or conversions.

Place kicking is the most visible of set plays in rugby, occurring with relatively frequency in an otherwise fluid moving sport. It therefore, provides an ideal opportunity to model a repeatable trial, with few important variables and come up with a ranking table for kicking ability.

The position from where kicks are taken are obviously the most important factors, but the player's preferred kicking foot and the side of the pitch from where the kick was taken can also impact on the likely success rate. The model is described in more detail here.

Over half of the points scored by each team in England's recent 21-16 win over Wales in the opening match of the 2015 Six Nations came from the boot. England's George Ford contributing 11 of their 21 points (and potentially may have scored 16 place kicked points), while Wales' Leigh Halfpenny adding 8 points (potentially 11) to the three from a Dan Biggar drop goal for the beaten hosts.

England crossed the tryline twice to Wales' sole touchdown, but the game remained sufficiently close for Brian Moore to describe Ford's 77 minute penalty as the most important kick of his career. The demand for instant sound bites contributes to such statements, but Ford's kicking career is defined by much more than a 40+yard attempt on a memorable night in Cardiff.

Ford's progression can be measured by comparing his kicking performance as a raw youngster for Leicester and England U20's to his more recent efforts in the Premiership with Bath.

91 typical penalty attempts from the 2011/12 season from the young George Ford yielded 58 successes. Had these kicks at goal been taken by the more accomplished version of the fly half from the 2014/15 Premiership season, an extra 14 kicks might have been landed, on average.

Similarly, 54 successes from 67 Premiership kicking attempts so far this season would likely have yielded just 42 successes if they had been taken by a player with the kicking ability of the younger Ford.

It shouldn't be a surprise that Ford has improved as a kicker from an 18 to a 21 year old. And we can use the respective models to simulate the range and likelihood of outcomes for the recent Wales England match if the kicks were taken firstly by the younger Ford and then the more experienced incumbent of the number 10 shirt.

In short, we can judge the impact of a team playing with both an accomplished kicker and also a less skilled one, albeit simply through youth and inexperience.

Using the likelihood that Ford and Halfpenny are successful or not with all of their their respective kicks, based on both the difficulty of the attempts on opening day and each player's historical success rates, it is possible to simulate the possible final scorelines by adding these probabilistic outcomes to the points scored from tries and drop goals.

Unsurprisingly, England win an overwhelming 97% of the matches that pit the current kicking talents of Ford against Halfpenny. The latter is currently the world's best kicker, while Ford is a very good international place kicker, but had more opportunities on the night. In addition England outscored their host in points scored from non place kicks.

However, if we use Ford's inferior kicking stats from his stint as an England Under 20 international to create his model, England now win just below 90% of simulations, drawing 2%. More significantly when the final kick from the actual game has been simulated after 77 minutes, Wales are either leading or within three points of England in 34% of the simulations when England's place kicking is inferior, compared to just 10% of the time when Ford is modeled at his current talent level.

This potentially changes the dynamic of the final three minutes. A third of the time Wales are either defending a lead or need just a converted penalty to rescue something from the game.

It is tempting to define a players career by the outcome of high profile, pressure kicks. But in truth, England gained their win in Cardiff by recognising Ford's development from a promising 17 year old to a twenty something with excellent international place kicking abilities.

The fall in England's win probability from a near 100% to just over 90% when they are forced to rely on a weaker kicker, highlights that in the modern game of rugby, the highest quality of place kicking appears to be a luxury you must afford.

Place kicking is the most visible of set plays in rugby, occurring with relatively frequency in an otherwise fluid moving sport. It therefore, provides an ideal opportunity to model a repeatable trial, with few important variables and come up with a ranking table for kicking ability.

The position from where kicks are taken are obviously the most important factors, but the player's preferred kicking foot and the side of the pitch from where the kick was taken can also impact on the likely success rate. The model is described in more detail here.

Over half of the points scored by each team in England's recent 21-16 win over Wales in the opening match of the 2015 Six Nations came from the boot. England's George Ford contributing 11 of their 21 points (and potentially may have scored 16 place kicked points), while Wales' Leigh Halfpenny adding 8 points (potentially 11) to the three from a Dan Biggar drop goal for the beaten hosts.

|

| Hands up if you're good enough to kick for Wales. |

Ford's progression can be measured by comparing his kicking performance as a raw youngster for Leicester and England U20's to his more recent efforts in the Premiership with Bath.

91 typical penalty attempts from the 2011/12 season from the young George Ford yielded 58 successes. Had these kicks at goal been taken by the more accomplished version of the fly half from the 2014/15 Premiership season, an extra 14 kicks might have been landed, on average.

Similarly, 54 successes from 67 Premiership kicking attempts so far this season would likely have yielded just 42 successes if they had been taken by a player with the kicking ability of the younger Ford.

It shouldn't be a surprise that Ford has improved as a kicker from an 18 to a 21 year old. And we can use the respective models to simulate the range and likelihood of outcomes for the recent Wales England match if the kicks were taken firstly by the younger Ford and then the more experienced incumbent of the number 10 shirt.

In short, we can judge the impact of a team playing with both an accomplished kicker and also a less skilled one, albeit simply through youth and inexperience.

Using the likelihood that Ford and Halfpenny are successful or not with all of their their respective kicks, based on both the difficulty of the attempts on opening day and each player's historical success rates, it is possible to simulate the possible final scorelines by adding these probabilistic outcomes to the points scored from tries and drop goals.

Unsurprisingly, England win an overwhelming 97% of the matches that pit the current kicking talents of Ford against Halfpenny. The latter is currently the world's best kicker, while Ford is a very good international place kicker, but had more opportunities on the night. In addition England outscored their host in points scored from non place kicks.

However, if we use Ford's inferior kicking stats from his stint as an England Under 20 international to create his model, England now win just below 90% of simulations, drawing 2%. More significantly when the final kick from the actual game has been simulated after 77 minutes, Wales are either leading or within three points of England in 34% of the simulations when England's place kicking is inferior, compared to just 10% of the time when Ford is modeled at his current talent level.

This potentially changes the dynamic of the final three minutes. A third of the time Wales are either defending a lead or need just a converted penalty to rescue something from the game.

It is tempting to define a players career by the outcome of high profile, pressure kicks. But in truth, England gained their win in Cardiff by recognising Ford's development from a promising 17 year old to a twenty something with excellent international place kicking abilities.

The fall in England's win probability from a near 100% to just over 90% when they are forced to rely on a weaker kicker, highlights that in the modern game of rugby, the highest quality of place kicking appears to be a luxury you must afford.

Saturday, 7 February 2015

OptaPro Analytics Forum.

Organised professional football has taken over a century to evolve to the heights of the Premier League, widely regarded as the most watched and discussed club competition in the world.

Similarly, Super Bowl One featured a marching band as half time entertainment, while SB49 was captivated by Katy Perry and two awkwardly dancing "sharks". Arguably another case of gradual advancement to current, new highs.

By contrast, OptaPro's second incarnation of their Analytics Forum, which took place on February 5th in the Senate House of the University of London, a stone's throw away from the British Museum, appears to have shunned incremental change in favour of one giant step forward.

Good as the initial event was, Thursday's occasion was almost flawlessly executed in bringing together the many diverse groups who have an interest in attempting to make some sense of the sport's data.

Expanding the venue from the basement rooms in 2014 to the light filled opulence of the first floor immediately answered the question, how many analytical bloggers can you fit in a lift? while also providing ample room for discussions to continue in the frequent breaks for refreshment.

The initial stars were the Opta judging panel, who selected a diverse and varied series of presentations, that combined innovation with potential application. And Opta themselves, particularly Simon Farrant and Ryan Bahia, who were responsible for the seamless, day long progression from podium to dinner plate to pub, despite the occasional intervention from errant technology.

The backbone of the day was the presentations, which will hopefully to quickly available on the OptaPro site and from a personal stance the highlight was being involved in producing (although thankfully not presenting) alongside Simon Gleave on the subject of ageing in players and age profiling teams.

Each presentation had merit, but two others demand a mention.

The day kicked off with Will Gurpinar-Morgan's polished delivery of the use and application of statistical analysis to define and categorise player types. Will ensured that we weren't witness to a cagey opening half hour and his content and delivery set the bar high for those who followed.

The highlight of the later sessions was Dan Altman's brilliantly constructed piece on going beyond shot locations to quantify scoring opportunities. Dan not only eclipsed my 4-30 am start by flying from and back to New York in a day, he also graciously signed my copy of his book and produced a genuine "wow!" moment when incorporating tracking data into his piece.

He also set the record for the quickest "goal" recorded by Opta during a presentation. I won't the spoil the joke, you will have to watch the video.

The biggest boon particularly for bloggers, is the chance to meet industry insiders and try to gauge how much, if any analysis of data is beginning to seep into the mainstream.

The potential to use numbers within the clubs themselves has been evident for sometime, but it was exciting to chat to guys from both the Premier League media and the print and online media and find them enthusiastic and keen to incorporate analytics into their own output.

The accusation is that analytics sucks the fun out of sport by reducing it to numbers, whereas the truth is that analysis actually helps to explain the inherent uncertainty that always exists in sports, especially one as low scoring as football and so, often raises the expectation for shock, surprises and excitement.

Gut reaction or intuition is often confounded by the data. So data driven conclusion, combined with a narrative can make ideal partners to inform and entertain in equal measure, rather than the hastily constructed sound bites that often dominate much of the coverage, but change with the whims of a single match.

That the appetite for an alternative approach appears to be growing, if slowly, is an encouraging sign.

Finally, Opta are to be congratulated for being prepared to risk staging an event on the basis of an abstract and largely unseen content. However, the size, variety of delegates and especially the distance many were prepared to travel was testament to the success of Thursday's event.

John Coulson and his team would have been hard pushed to improve on Thursday's experience....Maybe a firework display and laser light show from the BT Tower as the pub finally emptied.

Similarly, Super Bowl One featured a marching band as half time entertainment, while SB49 was captivated by Katy Perry and two awkwardly dancing "sharks". Arguably another case of gradual advancement to current, new highs.

By contrast, OptaPro's second incarnation of their Analytics Forum, which took place on February 5th in the Senate House of the University of London, a stone's throw away from the British Museum, appears to have shunned incremental change in favour of one giant step forward.

Good as the initial event was, Thursday's occasion was almost flawlessly executed in bringing together the many diverse groups who have an interest in attempting to make some sense of the sport's data.

Expanding the venue from the basement rooms in 2014 to the light filled opulence of the first floor immediately answered the question, how many analytical bloggers can you fit in a lift? while also providing ample room for discussions to continue in the frequent breaks for refreshment.

The initial stars were the Opta judging panel, who selected a diverse and varied series of presentations, that combined innovation with potential application. And Opta themselves, particularly Simon Farrant and Ryan Bahia, who were responsible for the seamless, day long progression from podium to dinner plate to pub, despite the occasional intervention from errant technology.

The backbone of the day was the presentations, which will hopefully to quickly available on the OptaPro site and from a personal stance the highlight was being involved in producing (although thankfully not presenting) alongside Simon Gleave on the subject of ageing in players and age profiling teams.

Each presentation had merit, but two others demand a mention.

The day kicked off with Will Gurpinar-Morgan's polished delivery of the use and application of statistical analysis to define and categorise player types. Will ensured that we weren't witness to a cagey opening half hour and his content and delivery set the bar high for those who followed.

The highlight of the later sessions was Dan Altman's brilliantly constructed piece on going beyond shot locations to quantify scoring opportunities. Dan not only eclipsed my 4-30 am start by flying from and back to New York in a day, he also graciously signed my copy of his book and produced a genuine "wow!" moment when incorporating tracking data into his piece.

He also set the record for the quickest "goal" recorded by Opta during a presentation. I won't the spoil the joke, you will have to watch the video.

The biggest boon particularly for bloggers, is the chance to meet industry insiders and try to gauge how much, if any analysis of data is beginning to seep into the mainstream.

The potential to use numbers within the clubs themselves has been evident for sometime, but it was exciting to chat to guys from both the Premier League media and the print and online media and find them enthusiastic and keen to incorporate analytics into their own output.

The accusation is that analytics sucks the fun out of sport by reducing it to numbers, whereas the truth is that analysis actually helps to explain the inherent uncertainty that always exists in sports, especially one as low scoring as football and so, often raises the expectation for shock, surprises and excitement.

Gut reaction or intuition is often confounded by the data. So data driven conclusion, combined with a narrative can make ideal partners to inform and entertain in equal measure, rather than the hastily constructed sound bites that often dominate much of the coverage, but change with the whims of a single match.

That the appetite for an alternative approach appears to be growing, if slowly, is an encouraging sign.

Finally, Opta are to be congratulated for being prepared to risk staging an event on the basis of an abstract and largely unseen content. However, the size, variety of delegates and especially the distance many were prepared to travel was testament to the success of Thursday's event.

John Coulson and his team would have been hard pushed to improve on Thursday's experience....Maybe a firework display and laser light show from the BT Tower as the pub finally emptied.

Wednesday, 4 February 2015

The Myth of the Eternal Goalkeeper.

It is not controversial to say that goalkeepers are slightly atypical of footballers in general. They have come in all shapes, but mostly one size (tall), appear to disproportionately prefer kicking with their left foot (although this is a personal observation that may not be backed by data), but most strikingly they appear to maintain their abilities into middle age.

Of the 19 seasons played by a footballer aged 40 or greater at mid season since 2002, 14 have been recorded to keepers. Many of these keepers have been solid regulars in their forties, rather than occasional beneficiaries of squad rotation or injury to a first choice alternative. 40 year olds accounted for 0.8% of the total seasons played by all keepers from 2002, but amassed 1.1% of the playing time for all keepers.

So the likes of van der Sar, Schwarzer and Friedel punched well above their weight/age and this has led to the common belief that goalkeeping is an eternal talent.

Of course, it is not true. Even the likes of Friedel have eventually called time on their top flight career. But their obvious presence in the lineup helps to perpetuate the myth that all keepers are age resistant, whereas attrition rates paint a very different picture. Of all keepers who played in the Premier League since 2002 around 90% of them had hung up their boots before the age of 40.

Friedel at 40 may have been good enough to take playing time from a younger, less talented alternative, but if we want to measure age related decline, especially in older groups of players, we need to compare Friedel to his younger self, rather than to a younger alternative player.

We did this in this previous post. Charting the change in playing time with age for individual players and then combining these changes for an overall age related decline or rise in allotted time.

Unlike baseball, where games and individual repetitive trials for the players are available in large numbers, an objective key performance indicator is largely unavailable for football. Therefore, change in playing time is used as a subjective, but informed proxy for talent.

The curve plotting increase or decrease in playing time charts the gradual shedding of appearance time by each keeper in the sample once they reach a subjective peak, including those 90% who fell by the wayside earlier than the likes of Friedel and Schwarzer.

Keepers appear to peak later than other positions. The previous post suggests 29 as a peak age. And so for completeness I've included similar plots for defenders midfielders and strikers.

At the moment players have been broadly categorised as defenders, midfielders and strikers, although further subdivision within these groups is obvious and desirable and the straight line plot would probably be better suited by a curved one. Similarly, a single, regressed figure to denote player talent or a single aspect of a player's ability would be preferable to the use of playing time.

But this approach does attempt to address the problem presented by the steady accumulation of more talented, but declining players populating the older aged groups in all positions and perhaps creating a more optimistic projection for older talent than is the case.

The age at which players in general from each positional group begin to lose playing time is 25 for strikers, 26 for defenders and 26.6 for midfielders.

Data on playing time has kindly been provided by Infostrada Sports with the help of Simon Gleave.

Of the 19 seasons played by a footballer aged 40 or greater at mid season since 2002, 14 have been recorded to keepers. Many of these keepers have been solid regulars in their forties, rather than occasional beneficiaries of squad rotation or injury to a first choice alternative. 40 year olds accounted for 0.8% of the total seasons played by all keepers from 2002, but amassed 1.1% of the playing time for all keepers.

So the likes of van der Sar, Schwarzer and Friedel punched well above their weight/age and this has led to the common belief that goalkeeping is an eternal talent.

Of course, it is not true. Even the likes of Friedel have eventually called time on their top flight career. But their obvious presence in the lineup helps to perpetuate the myth that all keepers are age resistant, whereas attrition rates paint a very different picture. Of all keepers who played in the Premier League since 2002 around 90% of them had hung up their boots before the age of 40.

Friedel at 40 may have been good enough to take playing time from a younger, less talented alternative, but if we want to measure age related decline, especially in older groups of players, we need to compare Friedel to his younger self, rather than to a younger alternative player.

We did this in this previous post. Charting the change in playing time with age for individual players and then combining these changes for an overall age related decline or rise in allotted time.

Unlike baseball, where games and individual repetitive trials for the players are available in large numbers, an objective key performance indicator is largely unavailable for football. Therefore, change in playing time is used as a subjective, but informed proxy for talent.

The curve plotting increase or decrease in playing time charts the gradual shedding of appearance time by each keeper in the sample once they reach a subjective peak, including those 90% who fell by the wayside earlier than the likes of Friedel and Schwarzer.

Keepers appear to peak later than other positions. The previous post suggests 29 as a peak age. And so for completeness I've included similar plots for defenders midfielders and strikers.

At the moment players have been broadly categorised as defenders, midfielders and strikers, although further subdivision within these groups is obvious and desirable and the straight line plot would probably be better suited by a curved one. Similarly, a single, regressed figure to denote player talent or a single aspect of a player's ability would be preferable to the use of playing time.

But this approach does attempt to address the problem presented by the steady accumulation of more talented, but declining players populating the older aged groups in all positions and perhaps creating a more optimistic projection for older talent than is the case.

The age at which players in general from each positional group begin to lose playing time is 25 for strikers, 26 for defenders and 26.6 for midfielders.

Data on playing time has kindly been provided by Infostrada Sports with the help of Simon Gleave.

Tuesday, 3 February 2015

From Raheem Sterling to Ryan Giggs.

At the age of 38 Ryan Giggs played 1480 minutes of Premier League football for Manchester United. A year later he managed only 1169 minutes and in his final season just 487 minutes. A remarkable footballer, but also one in decline.

Meanwhile, as Giggs' career was moving towards a managerial role, 17 year old Raheem Sterling's at Liverpool was moving in the opposite trajectory. 28 minutes of playing time in 2011/12 became 1752 in 2012/13 followed by a further leap to 2227 last season. A talent full of potential, and one that is currently in the ascendancy.

Regardless of their ultimate standing in the game, the career course for these two players over the last three seasons clearly demonstrates the fate of many sportsmen. Physical maturity coupled with greater experience initially brings improvement, denoted by increased playing time, but as the former begins to decline and the latter plateaus, even the most talented drop to the bench.

The winnowing of talent presents a problem at the extremes of playing age if we try to use the performance of these remaining talents to define the likely abilities of these older age groups. Giggs accounts for a quarter of the outfield players to have played at the age of 40 since 2002. Teddy Sheringham is another and Dean Windass and Kevin Phillips complete the list, although neither played very often.

So if we look at the just the performance of 40 year old outfielders, it is proportionally top heavy with very good players. Virtually all the players who could have played in the EPL at the age of 40 since 2002 have dropped out of the game.

However, if we use Giggs' falling playing time as a proxy for his decreasing ability to contribute to a Premier League team, his inevitable age decline is clear. Even if it is falling from greater heights than most other Premier League players.

This change in playing time as a player ages does open the way to chart the typical rise (in Sterling's case) and fall (in the older Giggs' case) in a Premier League player's capabilities, partly devoid of the surviour of the best which inevitably biases the smaller sample of older players.

r=-0.88

This alternative route to chart a player's age curve is perhaps best illustrated by the case of Premier League goalkeepers. Undoubtedly, keepers appear to peak slightly later than other positions, where physical endurance and speed may be more important. And some can play on into their late 30 or early 40's.

But as with Giggs, these older players are the exception and as with Giggs, they eventually see their playing time reduce as they are partly replaced by younger players approaching or reaching their peak.

In the plot above I have averaged the amount of increase or decrease in playing time for all Premier League keepers at different ages from 2002 to 2014. And the trend is clear. Keepers initially, on average, improve their playing time, peak and then begin to lose playing time as they decline.

The age at which improved playing time switches to a decline in playing time for Premier League keepers from 2002-2014 is a month short of 29 years old.

Despite the ability of some keepers to prolong their careers, and of the 85 keepers that potentially could have played on into their fortieth year, just 8 did, the average expectation for a Premier League goalie is that they will begin to show signs of a decline once they reach 29.

Similar delta curves, based on methods pioneered by Tom Tango can be produced for other positions and decline appears at progressively earlier ages, with forwards on average peaking around 25 years.

This study was undertaken with Simon Gleave, using data kindly provided by Infostrada Sports.

Meanwhile, as Giggs' career was moving towards a managerial role, 17 year old Raheem Sterling's at Liverpool was moving in the opposite trajectory. 28 minutes of playing time in 2011/12 became 1752 in 2012/13 followed by a further leap to 2227 last season. A talent full of potential, and one that is currently in the ascendancy.

Regardless of their ultimate standing in the game, the career course for these two players over the last three seasons clearly demonstrates the fate of many sportsmen. Physical maturity coupled with greater experience initially brings improvement, denoted by increased playing time, but as the former begins to decline and the latter plateaus, even the most talented drop to the bench.

The winnowing of talent presents a problem at the extremes of playing age if we try to use the performance of these remaining talents to define the likely abilities of these older age groups. Giggs accounts for a quarter of the outfield players to have played at the age of 40 since 2002. Teddy Sheringham is another and Dean Windass and Kevin Phillips complete the list, although neither played very often.

So if we look at the just the performance of 40 year old outfielders, it is proportionally top heavy with very good players. Virtually all the players who could have played in the EPL at the age of 40 since 2002 have dropped out of the game.

However, if we use Giggs' falling playing time as a proxy for his decreasing ability to contribute to a Premier League team, his inevitable age decline is clear. Even if it is falling from greater heights than most other Premier League players.

This change in playing time as a player ages does open the way to chart the typical rise (in Sterling's case) and fall (in the older Giggs' case) in a Premier League player's capabilities, partly devoid of the surviour of the best which inevitably biases the smaller sample of older players.

r=-0.88

This alternative route to chart a player's age curve is perhaps best illustrated by the case of Premier League goalkeepers. Undoubtedly, keepers appear to peak slightly later than other positions, where physical endurance and speed may be more important. And some can play on into their late 30 or early 40's.

But as with Giggs, these older players are the exception and as with Giggs, they eventually see their playing time reduce as they are partly replaced by younger players approaching or reaching their peak.

In the plot above I have averaged the amount of increase or decrease in playing time for all Premier League keepers at different ages from 2002 to 2014. And the trend is clear. Keepers initially, on average, improve their playing time, peak and then begin to lose playing time as they decline.

The age at which improved playing time switches to a decline in playing time for Premier League keepers from 2002-2014 is a month short of 29 years old.

Despite the ability of some keepers to prolong their careers, and of the 85 keepers that potentially could have played on into their fortieth year, just 8 did, the average expectation for a Premier League goalie is that they will begin to show signs of a decline once they reach 29.

Similar delta curves, based on methods pioneered by Tom Tango can be produced for other positions and decline appears at progressively earlier ages, with forwards on average peaking around 25 years.

This study was undertaken with Simon Gleave, using data kindly provided by Infostrada Sports.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)