Although most fans will have their attention focused firmly on Euro 2016, mid June is also an exciting time for followers of the promoted teams with the gradual release of the new season fixtures.

The greatest anticipation will be felt, along with a certain trepidation, among the supporters of Middlesbrough, Burnley and Hull, who reacquaint themselves with the newly enriched Premier League.

Promotion to the top tier no longer automatically offers short term monetary gain in exchange for regular defeats and a swift return to the Championship. But the regular success supporters became accustomed to in their promotion season will not be repeated in 2016/17.

The stark reality for promoted teams is that they will score fewer goals and concede more than they did in the Championship and most would happily take 17th spot come May 2017 and a chance to grow into their newfound affluent position.

A team scores goals through shot volume, shot quality, taking shots from better positions and then having players that can finish these opportunities consistently well.

These factors can be followed with increasing difficulty.

Volume merely involves counting, this is followed by an expected goals based model and finally a repeatable over performance in such a model that is unlikely to be wholly down to random variation.

The three promoted teams to the Premier League in 2015/16, Bournemouth, Watford and the subsequently relegated Norwich mustered nearly 2,200 non penalty goal attempts between themselves in their promotion year, but this fell to just 1313 during their Premier League campaigns.

Accounting for the greater number of Championship games, the rate per game fell from just under 16 to 11.5. Attempts allowed increased from 11.5 to 12.5 in the Premier League.

However, proportionally, goals scored and allowed fell and rose by larger amounts.

Goals scored by the promoted three fell by 45% in the next Premier League season compared to just a 27% fall for attempts and goals conceded increased by 55% compared to just a 5% increase for attempts allowed.

So based on the experience of last season there appears to be a disconnect between the change in goals scored when going from the Championship to Premier League and the change in attempts.

One possible cause for this disproportionately large change in actual goals across the two seasons is that promoted teams, as well as experiencing a change in shot volumes, will also find chances they both create and face will be converted at different rates in Premier League compared to the Championship.

Around 13% of the games the promoted trio played in the Championship was against sides who then fell into the third tier of Division One, while over 20% of their subsequent Premier League games would be against teams competing in the Champions League.

So it is fair to assume that the overall quality of opposition will rise sharply.

We may see if this is a reasonable assumption by adding a term to a shot model to distinguish between attempts made in the two different leagues for the three promoted sides to see if there is a significant difference in success rate when taking a shot in the Premier League and an identical one based on shot location in the Championship.

Based on the experience of Bournemouth, Watford and Norwich, the Championship was an easier place for them to convert similar chances than was the top flight.

Attempts from the same pitch location were less likely to result in a goal in the Premier League, more likely to be off target and more likely to be blocked compared to the Championship.

As an example, a shot from the edge of the box in the Premier League was converted 5% more often by the promoted trio in the Championship compared to identical efforts in the Premier League.

It is easy to surmise a range of contributing factors.

The level of opposition talent faced by these nascent Premier League sides in their promotion year on average was likely to be well below that faced subsequently.

This not only includes the level of goalkeeping talent, but also the ability of Championship sides to defend as a unit, close down potential assists and disrupt the creation of clear cut opportunities.

Although the promoted teams may be capable of creating chances, the level of defensive pressure during the shot may be significantly greater in the Premier League.

In short, the competitive environment faced by the promoted teams inevitably shifts upwards.

This reduced likelihood of converting chances compared to the experience in the lower grade of the Championship is repeated on the defensive side of the ball.

When faced with Premier League quality attacking, attempts conceded from identical pitch positions are less likely to be blocked than in the previous campaign, more likely to require a save and more likely to concede a score,

So if the most recent batch of promoted teams are typical, supporters of 2016/17's newly arrived trio can expect fewer attempts, with a reduced likelihood of scoring compared to comparable opportunities in the Championship and a similarly rough deal in defence.

Making survival, if they can emulate Watford and Bournemouth, all the more sweet come May 2017.

Saturday, 18 June 2016

Thursday, 16 June 2016

Is Wayne Rooney's England Career At An End?

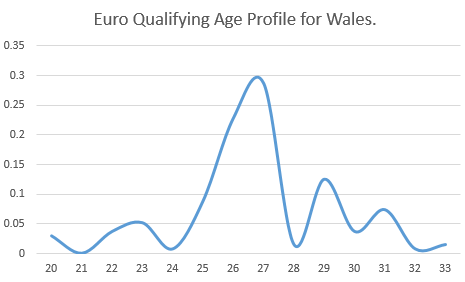

In this pre Euro 2016 post I looked at the age profile of all 23 qualifying teams in their group matches prior to the tournament and also posted the typical age graphs here.

The abilities of one peak aged player compared to another will obviously depend upon their innate talent levels.

A 27 year old Aron Gunnarsson may not be fit to wear the shirt of a 31 year old Ronaldo, but the physical advantages of having more peak aged players may tilt a contest or a compressed tournament schedule slightly towards those teams clustering around the ideal.

What is undeniable is that every participant in a sport based on both skill and physical attributes eventually reaches a point where their output no longer increases, but actively declines.

This cycle of improvement and then decline is most often illustrated in the normal curve of performance indicators, such as goals per game for strikers or a proxy, such as minutes played for players generally.

This approach is fine in a relatively large dataset, but may be much more noisy for individual players, where impact injuries, rather than wear and tear can remove large chunks of a season.

The above plot shows Alan Shearer's change in scoring input from his debut for Southampton to his final outing for Newcastle. It is inevitably noisy, but the general trendline indicates a season on season improvement until the line crosses the x axis and turns negative around the 1999-2000 season as Shearer approached 30.

June 2000 also marked Shearer's final appearance for England. So his international career ended at the point where it appears his club performances were beginning to gradually decline when measured by his goal scoring output. Shearer continued his club career until 2006.

England habitually have around 2 million eligible males between the peak age of 24 and 29 from which to source their premier international goal scorer. So it is perhaps not surprising that often their elite scorers rarely remain on the international stage much past their peak.

The populations of Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland are dwarfed by England's with the peak age male population ranging from around 190,000 for Scotland down through the Republic and Wales to a mere 60,000 for Northern Ireland.

It is also the case that other sports may compete for the same pool of talent.

Therefore, a much smaller selection pool exists for England's nearest neighbours and this may partly explain both Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland's less than ideal age profile from their qualification matches.

England has a selection pool that is 35 times the size of Northern Ireland's and as we can see from the table above, such countries often have to stick with their premier talent even in their declining years through lack of credible younger talent emerging.

The Republic's Robbie Keane is still a member of their Euro 2016 squad arguably over a decade since he reached his scoring peak. Scotland's Dalglish, Wales' Rush and Northern Ireland's Healy were each accruing caps 5 or 6 years beyond their best year.

Wayne Rooney is already an outlier among England's primary strikers having already played 4 years past his apparent scoring peak.

Had he played for any of the other home nations or the Republic it would perhaps be understandable if he had not yet been usurped by a less innately talented, but younger rival.

But to have survived as England's primary striker for so long, suggests either an unusual dearth of attacking talent from within a 2 million pool of resource or selection based on past, rather than present attributes.

With a lengthening queue of striking candidates, time may have finally caught up with Croxteth's child prodigy as the leader of England's front line.

The abilities of one peak aged player compared to another will obviously depend upon their innate talent levels.

A 27 year old Aron Gunnarsson may not be fit to wear the shirt of a 31 year old Ronaldo, but the physical advantages of having more peak aged players may tilt a contest or a compressed tournament schedule slightly towards those teams clustering around the ideal.

What is undeniable is that every participant in a sport based on both skill and physical attributes eventually reaches a point where their output no longer increases, but actively declines.

This cycle of improvement and then decline is most often illustrated in the normal curve of performance indicators, such as goals per game for strikers or a proxy, such as minutes played for players generally.

This approach is fine in a relatively large dataset, but may be much more noisy for individual players, where impact injuries, rather than wear and tear can remove large chunks of a season.

The above plot shows Alan Shearer's change in scoring input from his debut for Southampton to his final outing for Newcastle. It is inevitably noisy, but the general trendline indicates a season on season improvement until the line crosses the x axis and turns negative around the 1999-2000 season as Shearer approached 30.

June 2000 also marked Shearer's final appearance for England. So his international career ended at the point where it appears his club performances were beginning to gradually decline when measured by his goal scoring output. Shearer continued his club career until 2006.

England habitually have around 2 million eligible males between the peak age of 24 and 29 from which to source their premier international goal scorer. So it is perhaps not surprising that often their elite scorers rarely remain on the international stage much past their peak.

The populations of Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland are dwarfed by England's with the peak age male population ranging from around 190,000 for Scotland down through the Republic and Wales to a mere 60,000 for Northern Ireland.

It is also the case that other sports may compete for the same pool of talent.

Therefore, a much smaller selection pool exists for England's nearest neighbours and this may partly explain both Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland's less than ideal age profile from their qualification matches.

The Republic's Robbie Keane is still a member of their Euro 2016 squad arguably over a decade since he reached his scoring peak. Scotland's Dalglish, Wales' Rush and Northern Ireland's Healy were each accruing caps 5 or 6 years beyond their best year.

Wayne Rooney is already an outlier among England's primary strikers having already played 4 years past his apparent scoring peak.

Had he played for any of the other home nations or the Republic it would perhaps be understandable if he had not yet been usurped by a less innately talented, but younger rival.

But to have survived as England's primary striker for so long, suggests either an unusual dearth of attacking talent from within a 2 million pool of resource or selection based on past, rather than present attributes.

With a lengthening queue of striking candidates, time may have finally caught up with Croxteth's child prodigy as the leader of England's front line.

Wednesday, 15 June 2016

The Premier League Goal Scorers at Euro 2016.

The creme of the footballing elite may play in La Liga or Budgesliga, but there is no shortage of top class Euro 2016 talent who currently grace the Premier League.

18 countries currently engaged at France 2016 have at least one Premier League based squad member, led unsurprisingly by England (23), followed by Wales (13), Belgium and Republic of Ireland, both 12, down to Romania, Iceland, Czech Republic, Slovakia and Sweden with one each.

On the field, the tournament has followed the regular pattern of opening round matches by producing tight, low scoring contests, probably exaggerated by the possibility of knockout qualification for a third place group finish.

It is therefore natural that the focus in the later group stage games will fall on those players who are more likely to deliver goals for their country.

Analysing goal scorers has a series of components. Scorers are successful partly due to their ability to get on the end of lots of chances and then convert these chances with a modicum of skill.

So an ideal goal scorer's output is driven partly by shot volume and partly by shot conversion.

Often the latter is seen as the mark of a natural scorer, the ability to clinically dispatch a chance, even if a player has been largely anonymous in the match. While a player who consistently gets into good scoring positions without success, especially over the short term, is labelled profligate.

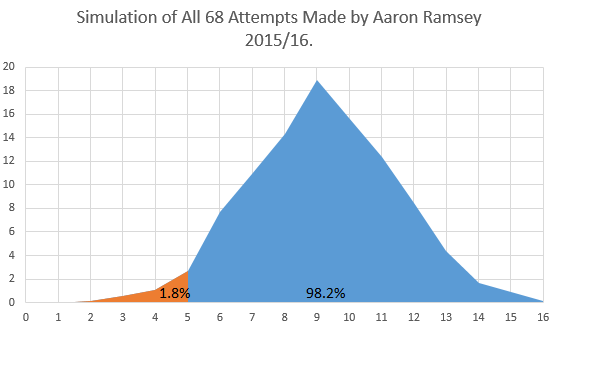

In the tables and plots below, I've looked at all Premier League players at Euro 2016 who have scored at least five goals in the last Premier League campaign and I've simulated the outcome of every non penalty goal attempt they made during the 2015/16 season.

This simulated model for each player using such inputs as shot type and shot location produces a distribution of likely outcomes based on the frequency and quality of their chances in 2015/16 paired with the finishing ability of an average Premier League player.

Wales and Arsenal's Aaron Ramsey scored five goals in 2015/16 from nearly 70 attempts. A poor haul from so many attempts, especially when the location is accounted for. Our modelled "average player" only scored fewer than Ramsey's five in 1.8% of simulations and would perform as well or better in a whopping 98.2% of such simulations.

Wonder kid, Marcus Rashford, also bagged five Premier League goals from considerably fewer attempts.

Mr Average would equal or better Rashford's haul in just under 5% of simulations and would fall short of his five goals ~96% of the time.

So if we take these simulation based conclusions at face value we may, selection dependent, have the best and worst Euro 2016 Premier League finishers facing off when Wales play England on Thursday afternoon.

Certainly Rashford has out performed his cumulative expected goals tally by as wide a margin as Ramsey has under performed his.

However, temping though it is to treat "advanced" stats with a degree of certainty, they should still be placed within a larger probabilistic context.

For one, Ramsey has an earlier body of work, where his conversion rates were much better.

Also if we model Ramsey's 2015/16 conversions from the basis of a slightly below average player and Rashford's compared to a slightly above average finisher, then both become less extreme outliers within two closely related classifications,

Expected goals do an excellent job of describing a player's season. Ramsey has been less than clinical, whereas Rashford has been writ large. But as a projection for the future, there is usually a large pull towards the average for the league as a whole.

The English striker is likely a better finisher than the Welsh midfielder, but the gap is unlikely to be as wide as their respective 2015/16 figures imply.

In the remaining tables I've simulated the Premier League attempts of all players at Euro 2016 who scored five or more actual non penalty goals.

Those whose red figures, denoting their actual goal tally, fall above the greened up most likely outcome from the simulation failed to catch the eye as a "clinical" finisher, while those whose red figure falls below green probably did.

The majority of the Euro 2016 player's 2015/16 Premier League achievements are within statistical touching distance of those expected from our "average player".

Kane, Rooney, Long, Benteke, Giroud, Arnautovic and Sterling are each cocooned within a sea of greened up average output.

Which may encourage you to lean towards attempt volume as a more important driver of actual goals than the perceived ability to consistently nutmeg the keeper once you get him in your sights.

18 countries currently engaged at France 2016 have at least one Premier League based squad member, led unsurprisingly by England (23), followed by Wales (13), Belgium and Republic of Ireland, both 12, down to Romania, Iceland, Czech Republic, Slovakia and Sweden with one each.

On the field, the tournament has followed the regular pattern of opening round matches by producing tight, low scoring contests, probably exaggerated by the possibility of knockout qualification for a third place group finish.

It is therefore natural that the focus in the later group stage games will fall on those players who are more likely to deliver goals for their country.

Analysing goal scorers has a series of components. Scorers are successful partly due to their ability to get on the end of lots of chances and then convert these chances with a modicum of skill.

So an ideal goal scorer's output is driven partly by shot volume and partly by shot conversion.

Often the latter is seen as the mark of a natural scorer, the ability to clinically dispatch a chance, even if a player has been largely anonymous in the match. While a player who consistently gets into good scoring positions without success, especially over the short term, is labelled profligate.

In the tables and plots below, I've looked at all Premier League players at Euro 2016 who have scored at least five goals in the last Premier League campaign and I've simulated the outcome of every non penalty goal attempt they made during the 2015/16 season.

This simulated model for each player using such inputs as shot type and shot location produces a distribution of likely outcomes based on the frequency and quality of their chances in 2015/16 paired with the finishing ability of an average Premier League player.

Wales and Arsenal's Aaron Ramsey scored five goals in 2015/16 from nearly 70 attempts. A poor haul from so many attempts, especially when the location is accounted for. Our modelled "average player" only scored fewer than Ramsey's five in 1.8% of simulations and would perform as well or better in a whopping 98.2% of such simulations.

Wonder kid, Marcus Rashford, also bagged five Premier League goals from considerably fewer attempts.

Mr Average would equal or better Rashford's haul in just under 5% of simulations and would fall short of his five goals ~96% of the time.

So if we take these simulation based conclusions at face value we may, selection dependent, have the best and worst Euro 2016 Premier League finishers facing off when Wales play England on Thursday afternoon.

Certainly Rashford has out performed his cumulative expected goals tally by as wide a margin as Ramsey has under performed his.

However, temping though it is to treat "advanced" stats with a degree of certainty, they should still be placed within a larger probabilistic context.

For one, Ramsey has an earlier body of work, where his conversion rates were much better.

Also if we model Ramsey's 2015/16 conversions from the basis of a slightly below average player and Rashford's compared to a slightly above average finisher, then both become less extreme outliers within two closely related classifications,

Expected goals do an excellent job of describing a player's season. Ramsey has been less than clinical, whereas Rashford has been writ large. But as a projection for the future, there is usually a large pull towards the average for the league as a whole.

The English striker is likely a better finisher than the Welsh midfielder, but the gap is unlikely to be as wide as their respective 2015/16 figures imply.

In the remaining tables I've simulated the Premier League attempts of all players at Euro 2016 who scored five or more actual non penalty goals.

Those whose red figures, denoting their actual goal tally, fall above the greened up most likely outcome from the simulation failed to catch the eye as a "clinical" finisher, while those whose red figure falls below green probably did.

The majority of the Euro 2016 player's 2015/16 Premier League achievements are within statistical touching distance of those expected from our "average player".

Kane, Rooney, Long, Benteke, Giroud, Arnautovic and Sterling are each cocooned within a sea of greened up average output.

Which may encourage you to lean towards attempt volume as a more important driver of actual goals than the perceived ability to consistently nutmeg the keeper once you get him in your sights.

Saturday, 11 June 2016

The Goal Keeping Class of 2015/16.

Goalkeepers, along with strikers are the easiest group of players for which to create individual expected goals metrics.

Expected goals models attach a probabilistic estimate of the outcome of every attempt on goal using a variety of variables, notably shot location and type.

Comparing a striker's actual scoring output against the "average player" outcome predicted from the model provides a simple benchmark for over or under performance and the same can also be done from the perspective of the keeper.

Often such results are condensed down to a single figure.

For example, a keeper who allows ten goals, when the cumulative total of the expected goals from all the on target attempts he has faced comes to eleven may be considered to have over performed by allowing 9% fewer goals than an average keeper might have.

While this approach conveys some information, it does lose a lot of the granular nature of the initial shot data.

In addition the distribution of expected goals over a range of shots having widely differing individual goal expectations is not always wholly represented by the cumulative total and sample size is also omitted in the catch all figure.

Running simulations of all the shots faced by a keeper maintains some input for both the quality and the quantity of the dataset.

Liverpool's Simon Mignolet had to deal with 112 attempts ranging from 1 in a 1,000 long shots to 9 out of ten near certainties. The cumulative expected goals total for all chances he faced came to just over 36 goals.

If we simulate every attempt faced by Mignolet using the output from a shot model based on prior seasons, we can see how likely it is an average Premier League keeper would concede 42 goals or worse. This was the record actually achieved by Mignolet in 2015/16.

That value comes to 9%. So, nearly 91% of the average keeper iterations result in fewer than the 42 goals Mignolet actually conceded. Therefore, Klopp's search for another keeper in time for 2016/17 is perhaps understandable.

By contrast, Fraser Forster faced 67 attempts, saving 50 and conceding 17 goals against an expectation of nearly 20. So an above average season long performance.

This can be quantified in a similar manner to Mignolet's under performance. Just as an average keeper would likely perform as bad or worse than Mignolet had in 2015/16 only 9% of the time, such a keeper would only perform as well or better than Forster in 22% of the iterations.

Models cannot capture every aspect of a chance, keepers may mature and decline with age and injury related fitness. But a probabilistic approach such as this can at least demonstrate that Mignolet's season was likely to have been a disappointing one and Forster's above par. Although based on this single season alone, there may be a 22% chance that he was just an average keeper buoyed by luck.

Expected goals models attach a probabilistic estimate of the outcome of every attempt on goal using a variety of variables, notably shot location and type.

Comparing a striker's actual scoring output against the "average player" outcome predicted from the model provides a simple benchmark for over or under performance and the same can also be done from the perspective of the keeper.

Often such results are condensed down to a single figure.

For example, a keeper who allows ten goals, when the cumulative total of the expected goals from all the on target attempts he has faced comes to eleven may be considered to have over performed by allowing 9% fewer goals than an average keeper might have.

While this approach conveys some information, it does lose a lot of the granular nature of the initial shot data.

In addition the distribution of expected goals over a range of shots having widely differing individual goal expectations is not always wholly represented by the cumulative total and sample size is also omitted in the catch all figure.

Running simulations of all the shots faced by a keeper maintains some input for both the quality and the quantity of the dataset.

Liverpool's Simon Mignolet had to deal with 112 attempts ranging from 1 in a 1,000 long shots to 9 out of ten near certainties. The cumulative expected goals total for all chances he faced came to just over 36 goals.

If we simulate every attempt faced by Mignolet using the output from a shot model based on prior seasons, we can see how likely it is an average Premier League keeper would concede 42 goals or worse. This was the record actually achieved by Mignolet in 2015/16.

That value comes to 9%. So, nearly 91% of the average keeper iterations result in fewer than the 42 goals Mignolet actually conceded. Therefore, Klopp's search for another keeper in time for 2016/17 is perhaps understandable.

By contrast, Fraser Forster faced 67 attempts, saving 50 and conceding 17 goals against an expectation of nearly 20. So an above average season long performance.

This can be quantified in a similar manner to Mignolet's under performance. Just as an average keeper would likely perform as bad or worse than Mignolet had in 2015/16 only 9% of the time, such a keeper would only perform as well or better than Forster in 22% of the iterations.

Models cannot capture every aspect of a chance, keepers may mature and decline with age and injury related fitness. But a probabilistic approach such as this can at least demonstrate that Mignolet's season was likely to have been a disappointing one and Forster's above par. Although based on this single season alone, there may be a 22% chance that he was just an average keeper buoyed by luck.

These plots can be summarised in spreadsheet format for all keepers from 2015/16.

The above heat maps illustrate the most likely number of goals conceded by an average keeper for attempts faced by the four keepers, The actual number of goals allowed by each keeper is highlighted in red.

Mignolet's poor season is shown by the small percentage of iterations that fall below his highlighted % figure.

Schmeichel's season was slightly above average, as his highlighted figure lies slightly above the most likely outcome of 40 goals conceded.

However, we perhaps shouldn't be too confident that his slight over performance is entirely down to talent. There is a greater than 30% possibility that an average keeper would achieve a results as good or better than Schmeichel did simply through randomness.

Lloris and Adrian also recorded above average shot stopping qualities, but again not by a large enough margin that we might confidently conclude that they are certainly superior to our average goal keeping benchmark.

The remainder of the keeping achievements from the 2015/16 season are summarised below.

The higher the red actual figure is above the darkest green formatting denoting the performance of an average keeper, the more likely the keeper is to have put in an above average performance.

And the lower a player's actual figure is below the benchmark average, the more likely he is to have exhibited below average levels of talent.

Brad Guzan's numbers were so bad he has broken the system, but as his colleague, Mark Bunn also scrapes the bottom of the barrel, it does seem possible that their car obsessed defence may have contributed levels of incompetence that was largely absent among other Premier League teams.

The above heat maps illustrate the most likely number of goals conceded by an average keeper for attempts faced by the four keepers, The actual number of goals allowed by each keeper is highlighted in red.

Mignolet's poor season is shown by the small percentage of iterations that fall below his highlighted % figure.

Schmeichel's season was slightly above average, as his highlighted figure lies slightly above the most likely outcome of 40 goals conceded.

However, we perhaps shouldn't be too confident that his slight over performance is entirely down to talent. There is a greater than 30% possibility that an average keeper would achieve a results as good or better than Schmeichel did simply through randomness.

Lloris and Adrian also recorded above average shot stopping qualities, but again not by a large enough margin that we might confidently conclude that they are certainly superior to our average goal keeping benchmark.

The remainder of the keeping achievements from the 2015/16 season are summarised below.

The higher the red actual figure is above the darkest green formatting denoting the performance of an average keeper, the more likely the keeper is to have put in an above average performance.

And the lower a player's actual figure is below the benchmark average, the more likely he is to have exhibited below average levels of talent.

Brad Guzan's numbers were so bad he has broken the system, but as his colleague, Mark Bunn also scrapes the bottom of the barrel, it does seem possible that their car obsessed defence may have contributed levels of incompetence that was largely absent among other Premier League teams.

Friday, 3 June 2016

Age Profile of All 24 Euro 2016 Countries.

Here's the proportion of playing time seen by age groups for all 23 qualifiers for Euro 2016 over the period of qualification. France, as hosts did not have to qualify, so their profile is simply taken from their final squad.

Peak age for performance may vary between player or position, but it tends to be from the mid to late 20's.

Averages are often used to describe a squad or team, but these are almost always misleading.

A team can have an average age of say 26 which is made up almost entirely of peak age players aged 26 years or it could have the same average age, but comprise of near equal numbers of players aged 21 and 31.

These distributions can be expressed numerically, but the visualisation of a plot based on proportion of playing time given to each age group probably best illustrates the career cycle of the current crop of internationals.

The team who have access to the biggest proportion of peak aged players at the 2016 finals is Ukraine.

Peak age for performance may vary between player or position, but it tends to be from the mid to late 20's.

Averages are often used to describe a squad or team, but these are almost always misleading.

A team can have an average age of say 26 which is made up almost entirely of peak age players aged 26 years or it could have the same average age, but comprise of near equal numbers of players aged 21 and 31.

These distributions can be expressed numerically, but the visualisation of a plot based on proportion of playing time given to each age group probably best illustrates the career cycle of the current crop of internationals.

The team who have access to the biggest proportion of peak aged players at the 2016 finals is Ukraine.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)